We’ve had some carers go sick so I’m helping out with the calls this morning. I like the change. So long as everything goes to plan, I won’t be called upon to make decisions, referrals, or any of the other worries that swarm in on you when you’re medically assessing a patient. In a lot of ways a care call is therapeutic – which I realise is easy for me to say, not having to do this day-in, day-out, chasing my tail across the city, stressing about keeping ahead, making time, all for a pittance.

Geoffrey’s house is on the kind of pristine new development where everything looks fake. I wouldn’t be surprised to be met at the door by a Playmobil figure. Instead it’s June, Geoffrey’s daughter, a middle-aged woman with an aura of stress so palpable you could use it to power the neighbourhood if you only had the leads.

‘Hello,’ she says, blinking emphatically. ‘Can you put these shoe covers on?’

The interior of the house is immaculate. Which explains the shoe covers. In fact, I’m surprised June doesn’t insist on a full body suit and respirator.

‘Dad’s still in bed,’ she says. ‘I’ll come up and show you what’s what.’

I follow her up the stairs and into a room brightly lit by the sun. Geoffrey is lying on his back in bed, his hands either side of his face, gripping the covers in that cliche, ‘man lying in bed’ style.

‘This is the carer, Jim,’ says June, running up the blinds. ‘He’s come to get you ready for the day.’

‘Oh, aye?’ says Geoffrey.

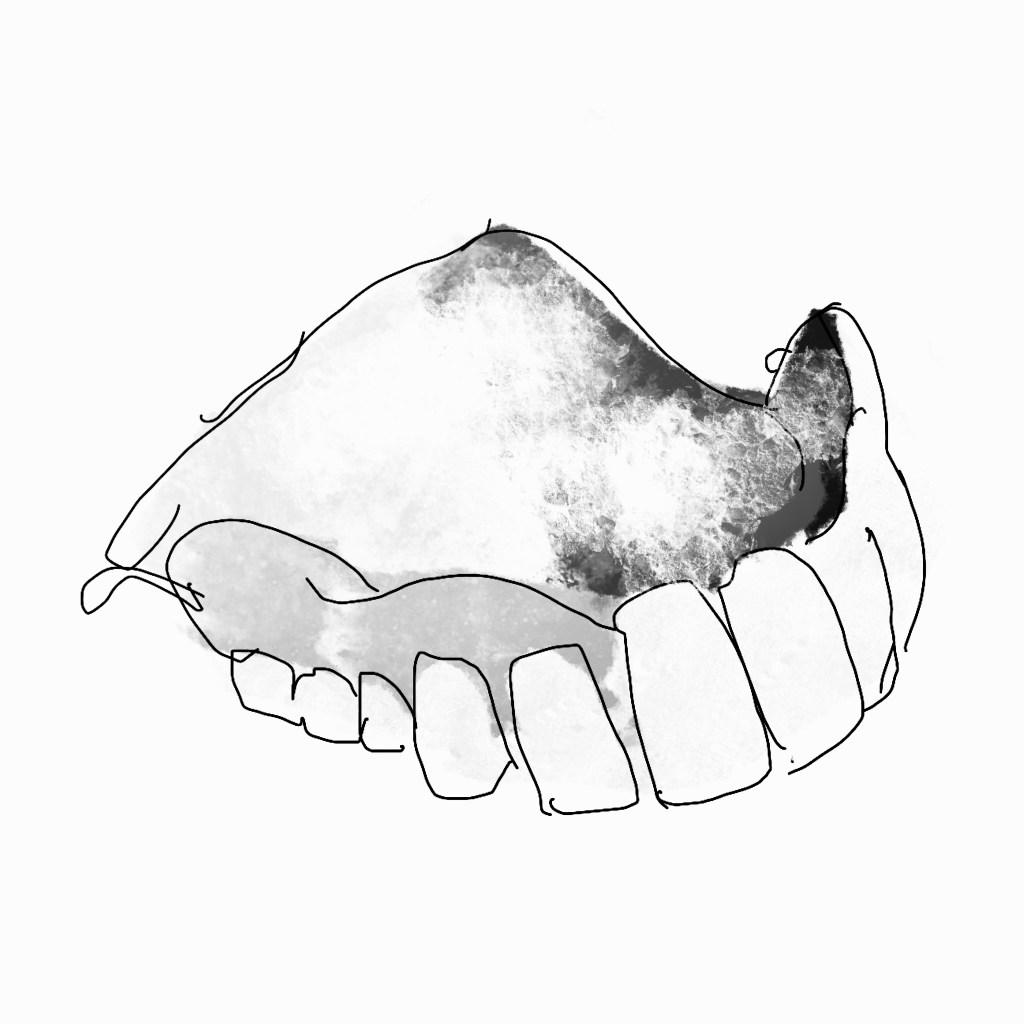

June shows me into the bathroom where everything is laid out: pink flannel for the face and top half, black flannel for the bottom and legs. Creams of various kinds. A comb. Toothbrush and paste. The toothbrush is enormous, like nothing I’ve seen before, a cumbersome red plastic instrument with bristles like a carpet brush on one side and on the other, the kind of circular brush that wouldn’t be out of place snapped onto a vacuum cleaner.

‘I’ll leave you to it,’ says June, before turning on the spot and hurling herself back downstairs.

The washing and dressing goes smoothly. Geoffrey is as organised as his environment, and apart from his great age and frailty, manages everything pretty much independently. We chat about this and that. Apparently – before he retired – he used to be a dental technician.

‘Oh!’ I say. ‘That’s interesting! I know a story about dental technicians!’

‘Hmm,’ says Geoffrey. I’m putting him into his tracksuit top so he can’t do anything else but listen.

‘You know that local natural history museum? Well the professor who used to run that place also helped the police out now and again. He was such an expert on bugs and beetles and skeletons and whatnot, they used to call him in for advice.’

‘Oh, aye?’ says Geoffrey. I hand him a comb to sort his hair out.

‘Well – this one time, they asked him to look at a building site. The builders were renovating an old house and they found a load of teeth in the basement, which looked suspicious. But when the professor examined them, he said it must have been the site of an old dentures workshop, and you could tell by the tiny holes near the root of the teeth, where they used to wire them together.’

‘Wire them…’ says Geoffrey. ‘Yes.’

I pass him his strange toothbrush.

‘Over to the expert!’ I say.

He carefully smothers the big brush with toothpaste, wets it under the tap, then starts busily scouring his teeth. It goes on for such a long time I’m worried he won’t have any teeth left. There’s a lot of spitting and hawking into the sink, followed by more brushing, followed by more spitting, and when five minutes have passed and I’m wondering if I should make an intervention, he unexpectedly puts the plug in the sink and starts filling the basin so full of cold water I’m worried it’ll overflow. But just as the level nears the top, he turns the taps off, then pulls out his top set, holds it under the water, and starts attacking it with the round bit of the brush. He scrubs it underwater for ages, pulling it out to inspect it occasionally, plunging it back under again to scrub some more, hawking and spitting into the basin the whole time. It’s a furious, all-elbows kind of procedure. I’ve never seen anyone clean their teeth like this before and I’m fascinated – so much so that I almost forget to catch him when he leans back unsteadily a few times.

‘There!’ he says, breathing hard, finally pulling the plug and inserting the top set back into position. ‘Now, then – what’s for breakfast?’