When I tell Mr Edwards the team is based at the old hospital, he straightens a little.

‘I know it well!’ he says. ‘I should do. I worked there all my life.’

‘Oh? What did you do?’

‘I used to keep an eye on the boilers, mostly. Other electrical stuff. A bit of everything, really.’

I’m kneeling on an inco pad on the floor. Mr Edward’s got his right leg propped up on a low padded stool so I can change the bandage. He shifts his leg to give me a little more room to work.

‘Better?’ he says, looking down at me with the gravitas of an old priest giving absolution.

‘Yeah, that’s very helpful. Thanks.’

‘That’s me, mate. Helpful to a tee.’

I’m sweating. I dab at my forehead with the back of my gloved hand. Maybe it’s the years of working in boiler rooms, or simply a function of his great age and reduced mobility, but Mr Edwards keeps his living room oppressively hot. The weather outside doesn’t help. The late October evening has drawn in, and a saturating fog billows along the street. To begin with, collecting the key from the keysafe and letting myself into Mr Edwards’ house felt like claiming sanctuary; five minutes later, I just want to curl up under the table, make a nest with his bags of creams and pads and medical supplies, and sleep.

‘That old hospital used to be a workhouse,’ he says.

‘Yeah – I heard that. It’s a fascinating place.’

‘That’s one word for it.’

‘Why? What word would you use?’

‘Haunted.’

‘Oh? Did you ever see anything?’

‘You wouldn’t believe me if I told you.’

‘Try me.’

He clears his throat; I sit back on my haunches to unwrap another bandage.

‘This is years ago, mind,’ he says, eventually. ‘Back in the sixties. That place was like a little village up on the hill then. It had everything – laundry, kitchens, workshops. All the wards of course, this and that. A self-contained village, with a big flint wall and a clock at the top of the old block by the road. When the Victorians built it they built it to last. Like a prison, really. Which in a way, of course, it was. If your crime was being poor. It’s been a few things in its time. Fever hospital. Lunatic asylum. Took in wounded soldiers from the Great War, and then after that they made it into a full time hospital. I started there when I come out of the army. I was only going to stay for a little bit till I found something better, but – you know how it goes.’

‘I certainly do.’

He fusses with his jacket, pulling it more tightly round himself.

‘The thing is, them Victorians built things sturdy. Especially the sewers. You could lose a coach and horses in the sewers under that old place. Honestly – it’s like a brick palace. I could walk you through most of it.’

‘I’d like that.’

‘If you did it on your own you’d never find your way out again. You wouldn’t like that so much.’

‘No. Probably not.’

‘Anyway. All the pipework went through these sewers along the ceiling. The boiler house they put in a kind of ante-chamber you had to access down a flight of brick steps. I didn’t mind it but some of the other guys got the heebie-jeebies. I suppose I was never much for that kind of thing – you know – worrying about ghosts and what have you. I had enough on my plate with the living! I’d be more scared by a knock on the door from the taxman, never mind some poor old fucker who had to rattle his chains and look miserable. None of that ever made much sense to me. Maybe I just never had the imagination.

‘The thing about that boiler room was – it was hot. And I mean proper hot. A kind of sticky heat that gets under your skin and makes your hands sweat. I’ve always liked a bit of heat, so I was in my element. I did my National Service in India. Loved it. Didn’t want to come back. Only I had to. So that was that. And you know what else used to like it in the boiler room?’

‘Ghosts?’

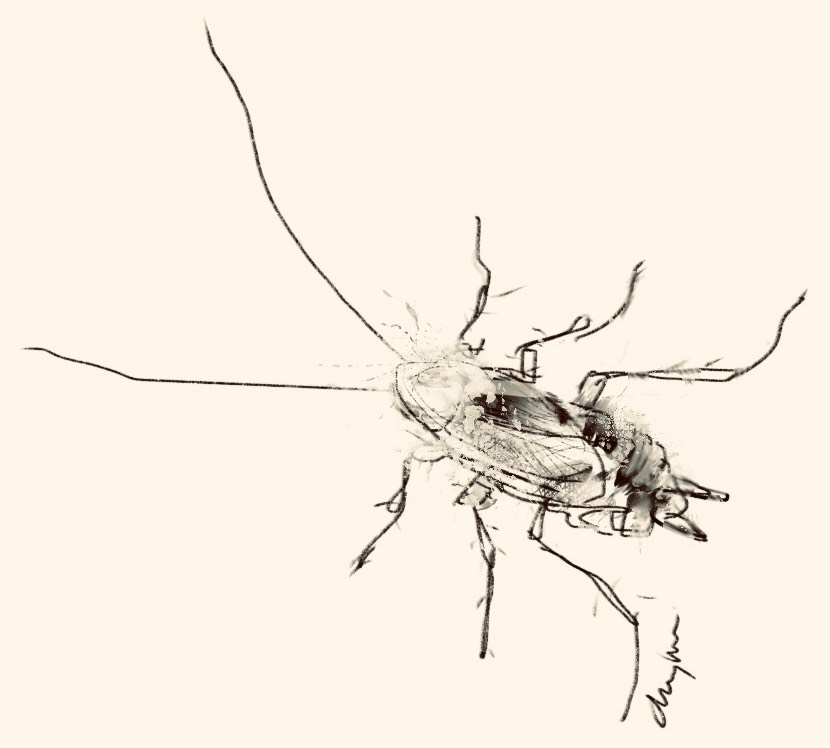

‘Cockroaches. They loved it down there. It was cockroach heaven. First thing in the morning, I’d open up the door, take a couple of steps down, put on the light. Straightaway they’d be this big, slippery, rushing kind of noise, like someone was emptying a tub of oyster shells over the floor. And you’d see them, all the cockroaches, scattering away back to the holes in the bricks that separated the room from the rest of the system.

‘One morning, just before Christmas, I had to go down the boiler room again. I opened the door as usual, took two steps down, and put on the light. This time, instead of the usual rushing sound, there was nothing, only a horrible kind of quiet, the kind you get before it snows. And standing in the middle of the room was this little boy.’

‘A boy?’

‘A tiny little thing, in a workhouse suit and cap. He was just standing there, staring up at me, with eyes half the size of his face. And before I could say anything he sort of collapsed – melted away – and there was that rushing noise again, and thousands of cockroaches running all over the floor, back into the bricks.’

‘That’s horrible!’

‘I was pretty shaken up.’

‘I bet! What did you do?’

‘I didn’t tell anyone. I said I felt ill and had to go home. They thought I was swinging the lead because it was near Christmas, but I daren’t tell ‘em the truth. I was dreading going back ‘cos I’d lost my nerve a bit. But things worked out. They’d decided to relocate the boiler ‘cos of ventilation issues. I only had to go down there a couple times more, but I never saw the kid again.’

‘Do you think he was warning you it wasn’t safe?’

‘Maybe,’ says Mr Edwards. ‘I don’t know. But like I said, it’s easy to get lost down there.’