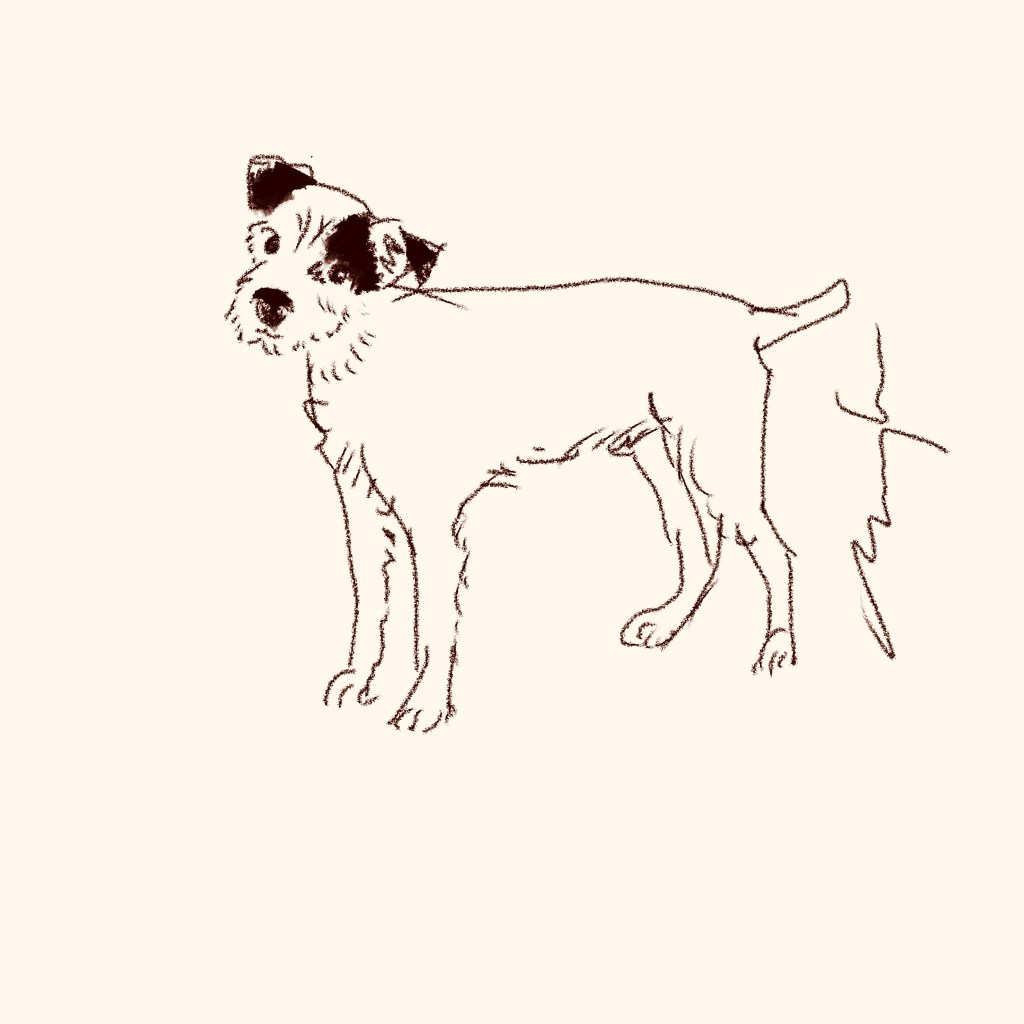

Rita stands in the doorway, shifting her slippered weight from side to side in an effort to stop Randolph the dog running out. Randolph is a Jack Russell. Almost completely white, but with splodges of black here and there on his head, as if it was late in the day when they made him and they ran out of paint.

‘Excuse the stickiness in Harry’s room,’ says Rita. ‘Only I spilled his Lucozade and it’s gone all tacky.’

They’re a perfect combination, Rita and Randolph. They could both have stepped out of a painting by Beryl Cook – the cheeky strippergran and her chubby lapdog. Except, you’d need a measure of reinforcement to take Randolph on your lap these days. His delicate legs don’t seem big enough for his hefty body, like someone no-nailsed the legs from a Chippendale desk onto a boiler. The most extraordinary thing about Randolph is his eyes, though. Made of clear blue glass. He stares up at me, and when I bend down to let him sniff my hand, he gives me such a sad and searching look I feel as if I’ve mind-melded with a Vulcan.

‘Harry’s through here,’ says Rita, leading us through the house, along a laminate wood hallway, Randolph’s paws making an emphatic snickering noise as he runs ahead, doing one of those comedy, sideways skids at the turn.

‘Careful!’ says Rita.

Harry is in bed watching the news channel with a frozen expression. Randolph tries unsuccessfully to leap up onto the bed, so Rita gives him a boost. Once he’s made it, Randolph licks Harry’s face, then turns to look up at us, as if to say: There! Ready for you now!

Rita is right about the floor. You have to consciously wrest your foot up from it to stop yourself from permanently sticking. My shoes feel so generously coated I’m tempted to try walking up the walls and across the ceiling – and I would have done it, too, if I could be sure Randolph wouldn’t bark and cause a rumpus.

‘I’ll get some soapy water on that,’ says Rita.

We’re halfway through the assessment when there’s a knock on the door. Randolph launches himself off the bed, crashing against a chest of drawers, then skittering out of the room.

‘Coo-ee!’ sings a woman.

‘That’ll be Joyce,’ says Rita. ‘The first thing she’ll mention is the Amazon boxes. You wait.’

Eventually a leaner and older version of Rita appears in the doorway. She dumps her bags in the hallway, comes into the bedroom to kiss Harry lightly on the forehead, then straightens up again and gives us all a smile-shrug combination that seems designed to say both ‘sorry I’m late’ and ‘isn’t that just like me.’

Then she takes a breath and looks straight at Rita.

‘I see you’ve been online again,’ she says.