Wanda is happily sawing away at a breaded cod fillet, arms tucked in, elbows up, her woolly hat pushed at an angle by the pillow back of her neck.

‘Sorry to interrupt your lunch,’ I say, coming into the room. ‘Bad timing!’

‘Sit on the bed,’ she says, pointing in that direction with a ketchuppy knife. ‘This won’t take me long.’

‘There’s a bit of paperwork to do, so I’ll get on with that whilst you finish up.’

She jabs up a nest of chips and only manages to get them in her mouth by moving her head from side to side.

‘Don’t give yourself indigestion,’ I say.

‘No,’ she says, ‘Mind you, I’m a martyr for that,’ half-choking as she struggles to get the words past the chips.

I pass her some water.

‘Thanks,’ she says, gulping it down – then sets back to finishing off the plate.

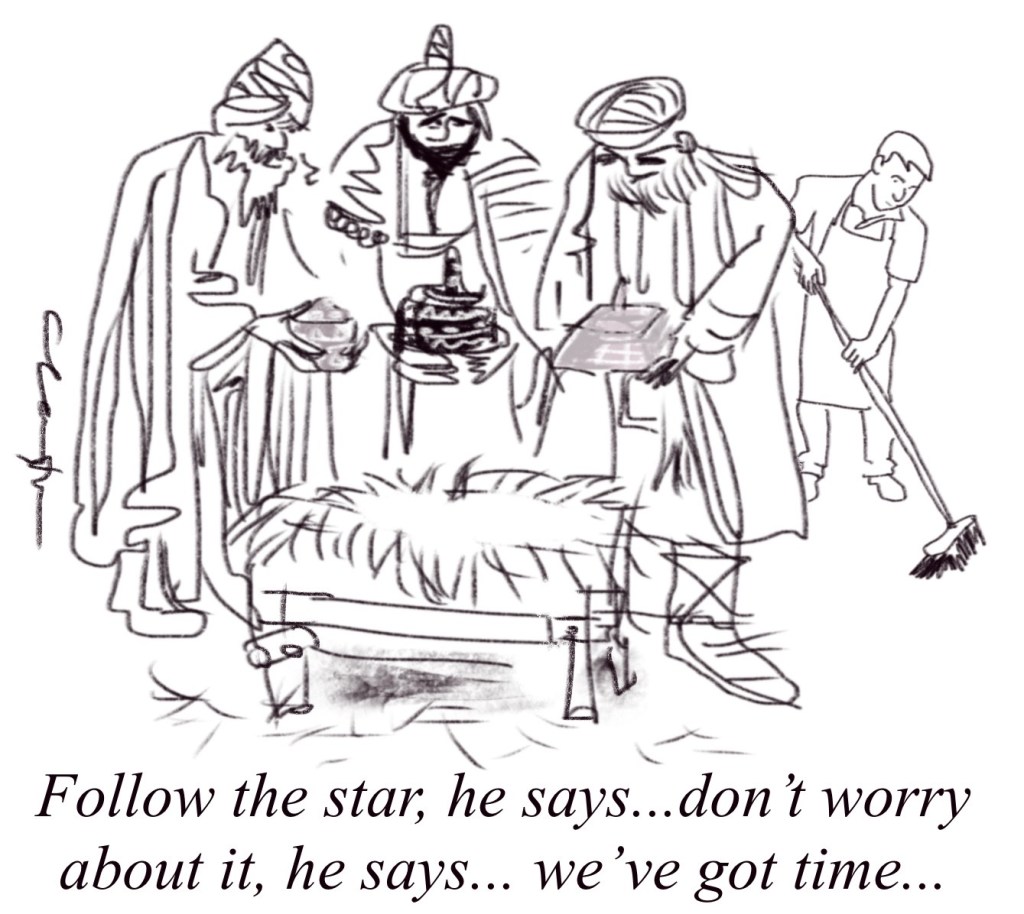

The ambulance service has referred Wanda to us. She’d had a couple of falls recently, minor injuries, observations fine but needed following up with nursing, therapy and so on. Wanda has some medical conditions that put her at more risk of falls, but at first glance I can’t see any more adaptations that could be made, and she lives pretty independently, so I’m not sure there’s much to be done. So long as everything checks out this visit, it might well be just a referral back to the care of her GP.

‘Done!’ she says, tossing the knife onto the empty plate with a clatter and a broad grin, like some kind of niche circus act.

‘Let me take that for you,’ I say. ‘Would you like to see the dessert menu?’

‘I’ll save that as my treat when you’re gone,’ she says. ‘So what’s this all about?’

I explain who I am, the team I work for and why the ambulance suggested we get in touch.

She sighs and brushes bread crumbs from her lap.

‘I don’t know why I’ve been falling so much lately. I suppose if you have one you’re more likely to have another.’

‘That’s true.’

‘I feel alright, though.’

‘Is there anything troubling you at all?’

‘The beetles,’ she says.

‘What beetles?’

She leans to one side and hauls out a mobile phone.

‘Just a minute…’ she says.

She curses and sighs as she tries to remember her pass code, and then navigate to the photos app. At one point she gets so frustrated she bangs the phone on the arm of the chair.

‘Do you want me to….?’

‘Just give me a minute!’ she says.

And then finally: ‘There!’

She hands me the phone.

It seems to be a close-up picture of tiny balls of carpet fluff.

‘I don’t get it.’

‘Zoom in!’ she says. ‘Slide your fingers!’ She makes a pinchy gesture in the air.

‘I know how to zoom in, Wanda,’ I say.

I zoom in.

‘I still don’t get it.’

‘Beetles!’ she says. ‘Look at the eggs! The legs!’

‘I can’t see it. Honestly – it just looks like fluff to me.’

‘The carpet’s infested. I see them all the time.’

She takes the phone back and shrugs.

‘They’re quite beautiful when they’re grown up, though,’ she says. ‘Blue-green backs, like little brooches. There’s one!’

She pushes herself up out of the chair and bends down to pluck something up from the carpet. I have to plant a hand on her shoulder to stop her from pitching head first into the dresser.

‘There!’ she says, brandishing another piece of fluff. She drops it into my palm, then sits back down again.

I look at it.

‘I’m really sorry, Wanda, but I think it’s just fluff.’

‘Look closer!’ she says.

I do, but it makes no difference.

‘The thing is, Wanda,’ I say, carefully giving it back to her – ‘if you look at anything close up it starts to look strange.’

‘Well maybe you can’t see it but I can.’

‘I’m not an expert on pest control,’ I say. ‘But honestly – it looks fine. Let’s do your observations and make sure everything’s okay in that department…’

It takes five minutes. There’s nothing out of the ordinary.

‘Any medication changes recently?’ I ask as I write down the figures.

She says that the doctor has adjusted a few things.

‘Why was that?’ I say.

‘Because they were worried I was having a psychosis or something.’

‘Oh yeah? In what way? What’s been happening?’

She pulls a face.

‘I’ve been seeing things. Especially at night. I’ll look out the window and there’ll be half a dozen people standing in the garden looking up at the window.’

She pauses to illustrate, tilting her head up but letting her jaw hang slack.

‘Like that!’ she says. ‘And I have to have the mirror on the floor before I go to bed because otherwise they keep peeking over the top of it and annoying me. Last night there was a woman standing out on the landing. And then when I’m sitting reading my Kindle, I’ll have a boy standing looking over this shoulder and an old man looking over the other.’

‘Does that worry you?’

‘Oh no! I’ve gotten used to it. I talk to them. I say What d’you think about that, then?’

She illustrates again, jabbing at her knee and glancing back over her right shoulder.

‘And what do they say?’

‘Nothing! They never talk!’ she says, looking at me again. ‘But I don’t mind. I like the company.’

She balls her fist and taps herself a couple of times on the centre of her chest.

‘Oof!’ she says, puffing out her cheeks. ‘I shouldn’t have had all them chips. I’ll pay for that later.’